Greeks are heading for the ballots in a rather subdued campaign atmosphere – even the seven-leader televised debate failed to capture the excitement of a public that looks more and more cynical after five national elections in the last 17 months.

The policies for the next parliamentary term are already in place – they are dictated by the €86-billion bailout agreement negotiated at the eleventh hour by Alexis Tsipras and approved in parliament by most of the opposition.

This certainty deprives the campaign of the fundamental dichotomy of the last five years: whether the country will escape the economic crisis within the EU-IMF-imposed adjustment programmes or seek alternatives that would remove it from the European core.

As things stand, Tsipras’ left-wing Syriza and his coalition partner, Panos Kammenos’, Independent Greeks, have now forcibly joined the camp of EU loyalty.

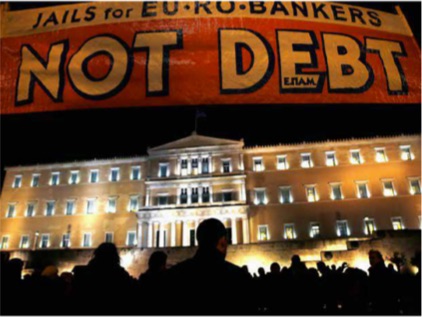

The anti-austerity, anti-European wing now consists of People’s Unity, the party formed by Syriza’s radical left-wing splinter faction, the Communist Party and neo-Nazi Golden Dawn. Combined they are not projected to receive more than 20% of the popular vote at most, which seems to settle the dispute on strategic orientation that marked the previous six years of the crisis.

A large part of the electorate appear to have been persuaded that painful policies are indeed necessary.

Tsipras’ decision to abandon his anti-austerity hard line and sign a third bailout, after a protracted six-month negotiation that ate away most economic gains made in the previous period, appears to have persuaded a large part of the electorate that painful policies are indeed necessary. Something similar had happened a few years ago, when Antonis Samaras, then leader of conservative New Democracy, was forced to make a similar U-turn.

Hence, the main issue that must be settled by voters on September 20 is the composition of the government coalition that will undertake the unenviable task of implementing three more years of economic austerity and unpopular reforms to the state and markets.

For the first time in history, ND appears content with the role of leading a coalition, as this is the election aim declared by its caretaker-turned-permanent leader, Vangelis Meimarakis.

Europeans appear certain that Tsipras will be the key person in implementing the programme

On the other hand, Tsipras aims for an overall House majority that would allow him an unhindered full four-year term in government. If opinion polls are not way off target, the election result will teach him a hard lesson in consensus politics, forcing him to work towards a coalition with some of the people he still denounces as untouchable.

Europeans appear certain that Tsipras will be the key person in the process of implementing the programme; as he is the one who negotiated the agreement, they believe he is the one who can best convince the public of its necessity, especially given his past anti-bailout rhetoric.

An accepted inevitability

In any case, the notion of a broad coalition, as the optimal agent to carry though painful but indispensable policies, has been gaining ground to the point of being recognised as an inevitability, both in Greece and abroad.

Greek voters look set to offer their seal of approval to the idea and determine a new political and parliamentary balance of power. Then it will be up to politicians to sort out the mechanics of a new style of governance that will attempt to lead Greece out of the ordeal.