Βy John Psaropoulos

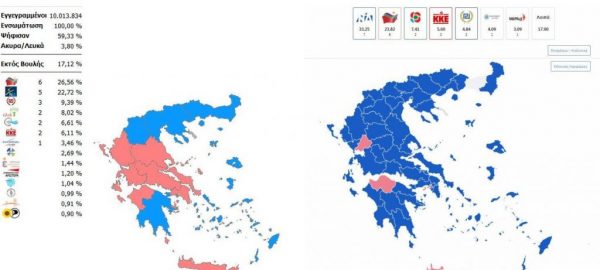

Αthens, Greece – Voters punished the ruling Syriza party for broken promises in Sunday’s European Parliament election. The conservative New Democracy party’s nine-point lead over Syriza was so devastating, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras announced a snap general election that is expected to be held at the end of June, four months early.

“The result … is not up to par with our expectations,” Tsipras said.

The Greek leader was referring to more than $1bn worth of handouts he had announced three weeks before, in the form of a halving of sales tax in supermarkets and restaurants, and a bonus pension. Voters were seemingly not impressed by the measures.

Tough times

“Tsipras’ handouts acted as a boomerang,” says Nikolaos Nikolaidis, a lawyer with good connections inside the conservative party. “If you look at how pensioners voted, the bonus pension was more of an annoyance. It reminded them of all that had been taken away in previous years. It was also announced just before the election and was clearly connected to it.”

Greece lost a quarter of its economic output during its eight-year depression. Unemployment peaked at 28 percent in 2013 and remains at 19 percent. Economists record it as the worst contraction of any developed economy since World War II. And although a recovery did begin under Syriza, it has been weak. The economy grew by less than two percent in 2018, a performance it is set to repeat this year.

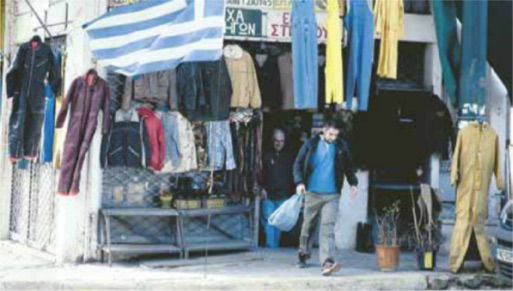

“I see conditions in the market. When you cut people’s pensions and squeeze them economically, I see a fall in sales,” fishmonger Thanasis Kazlaris told Al Jazeera as he shovelled whitebait into a paper cone for a customer. “The taxes don’t help. Sales tax had gone up a lot.”

Last year’s Prespes Agreement, whereby Greece recognised its northern neighbour as North Macedonia, also undercut Syriza’s popularity.

In the same central Athens market, chicken farmer Angelos Mavroeidis was unsurprised by the result. “I haven’t gone to university. I’ve only done high school. There are economists who know these things better. Something has to happen. We have to have an economy like America’s, like Australia’s, like Britain’s. These aren’t things that have to be reinvented,” he said.

Last year’s Prespes Agreement, whereby Greece recognised its northern neighbour as North Macedonia, also undercut Syriza’s popularity because it recognised a Macedonian language and ethnicity. In the northern Greek provinces of Macedonia, Thessaly and Epirus, New Democracy won simultaneous elections for regional prefects in the first round.

A series of unfortunate events

When Greeks first elected Syriza in January 2015, the party promised to end austerity and rip up Greece’s onerous agreements with its creditors. Instead, it agreed to a third bailout loan which carried further cuts to pensions and higher taxes.

Syriza, which following the agreement called and won snap elections in September 2015, managed the economy with high taxes and high surpluses. It was able to keep up payments to its creditors – who are chiefly its Eurozone partners – and regain market trust, graduating from Greece’s eight-year fiscal adjustment programme last year. But this came at the cost of low growth and stubbornly high unemployment rates.

“Taking into account the policies they have been implementing for four years, [Syriza] did pretty well. They have not vanished as other parties have vanished.”

The result was a complete reversal of the European elections in 2014 when the ruling conservatives saw Syriza surge almost four points in front of them. Now, as then, the EU elections have acted as a weathervane, showing who is likely to come to power next.

“Taking into account the policies they have been implementing for four years, [Syriza] did pretty well,” says Panos Polyzoidis, a political observer and analyst. “They have not vanished as other parties have vanished.”

Polyzoidis was referring to The River, a centre-right reformist party, as well as the Centre Union, a populist party, and the nationalist Independent Greeks party, Syriza’s erstwhile coalition partner. None won any seats in this election and are unlikely to survive the next general election.

New Democracy‘s high score of 33.2 percent of the vote suggests it might yet energise a greater voter base in the coming month. It would need about 40 percent to rule outright, without a coalition partner.

“This will be a springboard for New Democracy,” Polyzoidis says. “It could build on that spectacular victory and possibly even flirt with an absolute parliamentary majority.”

Nikolaidis agrees. “What made the difference was that New Democracy pulled voters from other parties and especially Syriza,” he says. “Fifteen percent of Syriza’s 2015 voters went to New Democracy. And I don’t think it has exhausted the potential there.”

The four-percent wager

New Democracy leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis has promised a restart of the economy. He says he will lower tax on businesses from 29 percent to 20 percent in two years and lower income tax on farmers from 22 percent to 10 percent.

Mitsotakis’s economic plan largely hinges on a key promise to negotiate a new deal with Greece’s creditors

He also says he will seek to create 700,000 new jobs in five years and has pledged to bring home at least half a million of the 860,000 skilled workers who, according to the Hellenic Statistical Service, have left the country since 2009.

“The whole scenario of lowering taxes and social security contributions, and increasing wages – that is all founded on the assumption that the economy will achieve an annual growth rate of four percent,” says Polyzoidis. “Personally I see that as difficult.”

Mitsotakis’s economic plan largely hinges on a key promise to negotiate a new deal with Greece’s creditors. That would allow him to spend less on repaying external debt and keep more money in the economy for reinvestment.

Envisioning a “secure, extrovert and prosperous” Greece last September, Mitsotakis said “all the other countries that underwent crises have made it”.

“Some, like Portugal, Spain and Cyprus, are growing at three or four percent,” he said. “Others, like Ireland and Romania, at six or seven percent. What do they have that we don’t? … Nothing we can’t do too, if we decide to do it and make the effort.”